Released: Aug 28, 1987

Version played: Retranslated (2012)

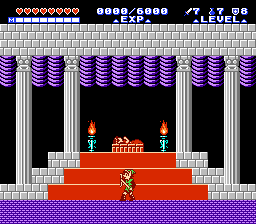

If Zelda II is Dark Souls, a precise hybrid of RPG, adventure game and dungeon crawler that constantly propels the player to its next exciting encounter, then Castlevania II is Dark Souls II, a game which turns its systems inward against itself to invert the usual emotional journey of RPG game design. Zelda II is brutally hard, but levelling up gives you an immediate and satisfying increase in power. Castlevania II is easy, and levelling up a form of controlled tedium, as you balance gains in EXP and Money to ensure you always have enough to buy everything in the next town.

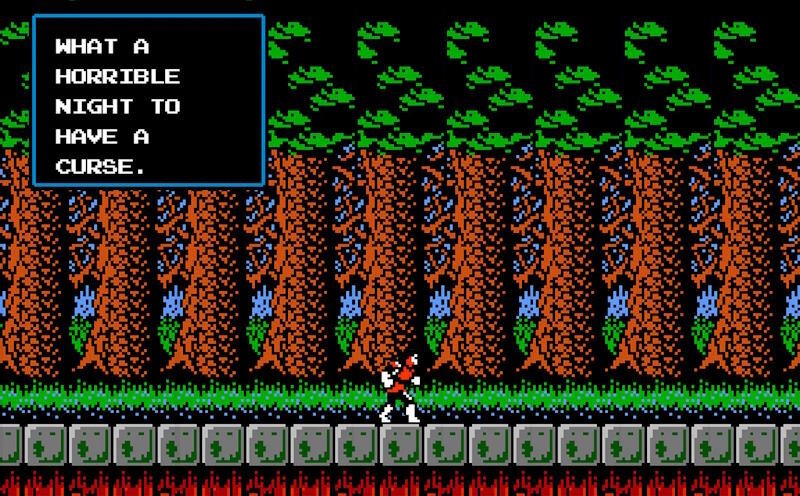

It would be easy to say such design is a mistake, why would the sequel to a hard as nails and constantly exciting masterpiece like Castlevania intentionally introduce elements of boredom? But the game’s most famous line proves the opposite. What a horrible night to have a curse. The night falls, the enemies get stronger, and most importantly, the towns become swarmed with monsters. You cannot rest, you cannot buy upgrades, you cannot obtain hints from the townsfolk; they’re all hiding behind closed doors anyway. What you can do, however, is wait. Find a nice grinding spot. And turn the demons of Evil into currency, one whip at a time.

Castlevania II is not a story of triumph, adventure, or even as its localised name would imply really a quest. It is the story of a curse. An extremely literal curse in Simon’s case, but also far more pervasively the sense of a truly dead world rotting from within. The monsters stay away from towns only when the preists are awake to pray. The townsfolk drop hints and give moments of levity, but are ultimately all trapped and hiding in their boarded up terraces, brown and grey and faded. These towns live under the shadows of grand aristocratic mansions which house only skeletons both animated and not, corpse filled dungeons that haven’t been put to use in however many years. Inside these monumental palaces the only objects of reverence and signs of intention at all are Dracula’s body parts, placed on Altars of worship to hasten his return.

It all adds up to a game that is extremely evocative and haunting. There is no onscreen cult, or dark wizard, or power mad scientist here to resurrect dracula, perhaps wishing to pay him tribute. Instead all we know is Dracula has allies, perhaps they are the monsters, perhaps the owners of the mansions; but why then is there no sign of life? No other signs of civilization or intent or planning. The monsters are all mere beasts, the mansions mere facades, yet someone or something placed Dracula’s body parts there. Obviously there is no answer, this isn’t a puzzle and just a tonal effect from the game’s NES presentation, but I really like the atmospheric effect it creates. The peasants are oppressed not by the church or by the king, but by the empty signifiers of aristocracy, with no way to know there are only bones inside. It’s an atmosphere that won’t truly become popular until the Souls games double down on this form of storytelling through absence, but thankfully this game was created in the 80s so I can’t read ten million item descriptions explaining the history of Rover Mansion. It simply is.

The game saves its best trick for last, with a completely silent walk through Dracula’s Castle leading to a total pushover of a Final Boss. Castlevania II takes the wind out of the sails both as an RPG about gaining power and as a blood-pumping action game with this deflating anti climax, that unless you were aware of the in-game time limit beforehand, almost inevitably also results Simon sealing the curse yet dying from his wounds.

This makes Castlevania II a trailblazer not just in how it’s one of the first sequels to go from linear action game to open world RPG, but also in the soon to be overcrowded line of you enjoy all the killing metacommentary. Pretty much twenty years ahead of its time. But while audiences didn’t wholly accept Castlevania II it’s alright because they did pivot to instead making the greatest 8 bit action game of all time instead.