Released: Dec 31, 1986

Version played: The Bard’s Tale Trilogy (2018)

I do not have much to say about The Bard’s Tale II.

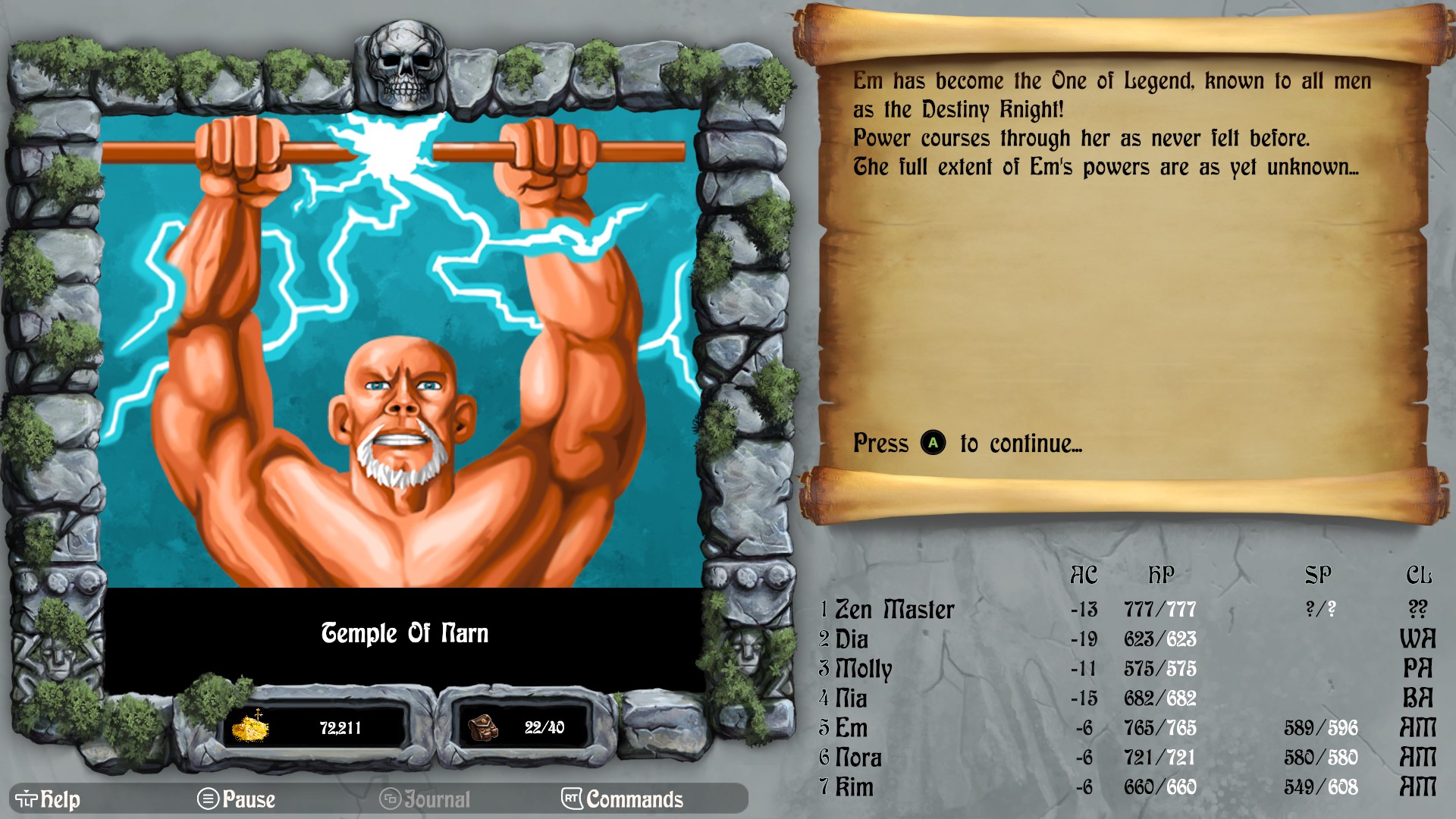

The Destiny Knight is not a bad game, but it is a much worse game than its predecessor, despite key steps forward in basically every area. There are more dungeons, there are more towns, more puzzles and more story. By which I mean there’s like three lines of story. But one of them is a plot twist! That ain’t nothing in 1986.

And it’s a game that feels like it never ends. Not just because it is much longer, but because every battle is harder and more involved. There’s no push and pull, no difficulty spikes and cliffs, the tightening of the balance between your party and the enemies has somewhat unintuitively made the game much worse.

How much slack should you give your players is a question that can never be resolved, for every player is different. Some want to grind and overpower the whole game, some want to be challenged in every fight. I tend to prefer a mix of both, with a leaning towards easier individual fights when the challenge is dungeon exploration and resource management, and tough mechanical puzzles of skill and knowledge in boss fights. I am a simply raised by Final Fantasy, I am who I am. The Destiny Knight instead greatly expands the enemies options while not really giving you many more tools to deal with them. There is a final Archmage class, and it’s helpful, but its tools are nowhere near enough to walk over the mobs here, spread out as they are among 90’ sized battlefields. This means every fight you have to be at the top of your game, and these dungeons go on forever. If Dragon Quest is no mechanics and all pacing, the language of the genre repurposed to punctuate and heighten moments along a simple hero’s journey then The Destiny Knight is the exact opposite, a gruelling monotomous slog.

The dungeon design is actually greatly improved, with the increased number of dungeons meaning each can be designed around its own mechanical gimmick. There are some really fucking terrible dungeons in here, but they are identifiably terrible, in a Zeldaesque way. No one likes the one where you can’t use magic. But at the same time, there’s a dungeon where you can’t use magic.

Each dungeon culminates in a Trial, which is one of those 80s sequel ideas that people call experimental when trying to be nice. These are part riddle-solving, part exploration, part combat and sometimes part plain old luck. The riddles are so much more obtuse than in the first game that in this modern age you will simply be looking these up 80% of the time, but even that can’t help much when a Trial requires you to complete a series of steps seven times in a row with no feedback that it’s working til the entire process is complete. I like to think of myself as open hearted when it comes to playing old games, and I think I certainly am, but sometimes you have to summon your inner Angry Video Game Nerd. What, indeed, were they thinking?